Artist of the Year 2020: Seijun Suzuki

It’s said that “film is a director’s medium”. This project, Artist of the Year, is built around that premise by focusing on one director’s work for a full year. While watching through Seijun Suzuki’s films, it became clear that I had at least five actual artists of the year.

Naturally, Suzuki directed all 27 films in this project. Akira Suzuki edited at least 24 of the 27.0 Shigeyoshi Mine (9 films) and Kazue Nagatsuka (8 films) were cinematographers and consistent collaborators throughout the Nikkatsu years. Nagatsuka additionally worked on the first two Taisho Trilogy films.

If any collaborator were to be called out as deserving of Artist of the Year themself, though, it’d be Takeo Kimura. He served as art director on 11 of the films, and writer on 2. He played in a role in every Suzuki film during his peak at Nikkatsu, stretching from 1963 until Suzuki’s firing in 1967. The two later collaborated on my three favorite post-blacklist films (Zigeunerweisen, Pistol Opera, Capone Cries a Lot).

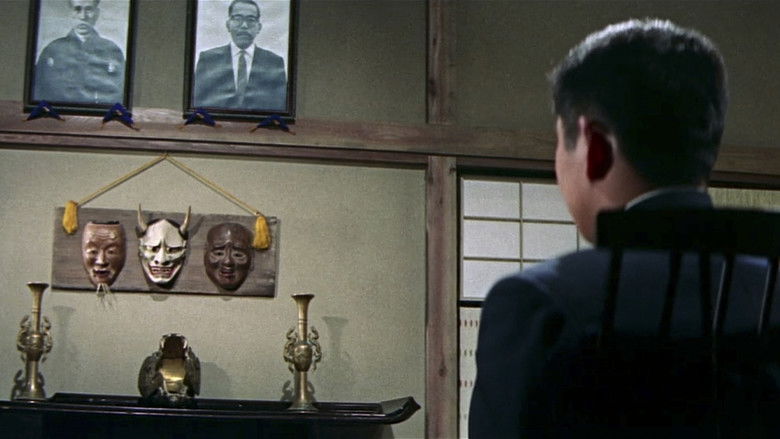

The films in this period encompass most of Suzuki’s well renowned films, and easily cover the ones most often cited for their “psychadelic” or “surreal” color usage. That isn’t to say that this was all Kimura’s doing. As early as 1961, with Tokyo Knights, we see a usage of elaborately colored sets and lighting changes. What makes Tokyo Knights different from the later collaborations with Kimura, where this seed of a style would blossom, is that the more theatrical elements are grounded in an actual Noh performance. Textual explanations for style would be shed as they worked together more.

In 1963, the first year of Suzuki’s collaboration with Kimura, Kanto Wanderer featured conspicuous theatrical lighting changes that mirror the protagonists emotional state. Tattooed Life’s climax primarily occurs in a side-on view calling to mind an audience’s view of a stage production, complete with a shift to spotlights. Tokyo Drifter in many ways is the endpoint for this style, all white plaster to reflect whatever lighting the moment calls for.

The strongest films from this year’s project were the joint Suzuki-Kimura productions. Enough so that Kimura probably deserves his own page.

0 I say at least since crew credits in English are sometimes spotty for the less discussed films. The Nikkatsu website is pretty thorough with credits (example), and I tried as best I could to copy those into TMDB.

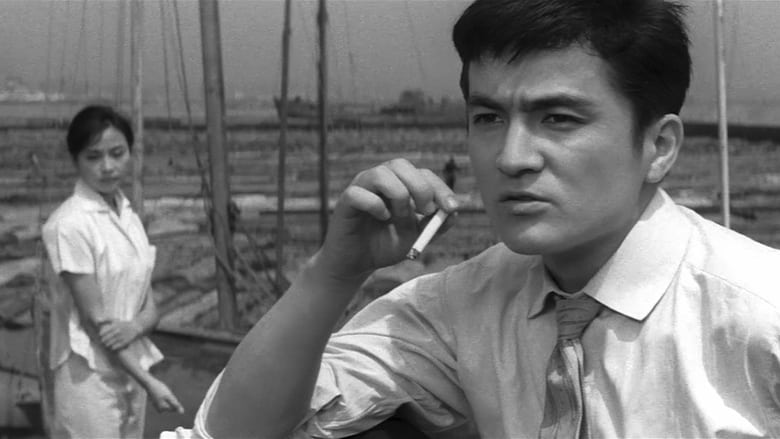

俺たちの血が許さない Our Blood Will Not Forgive (1964)

So many interesting visual sequences here, some of which individually make returns in later films, but the density of them makes this special.

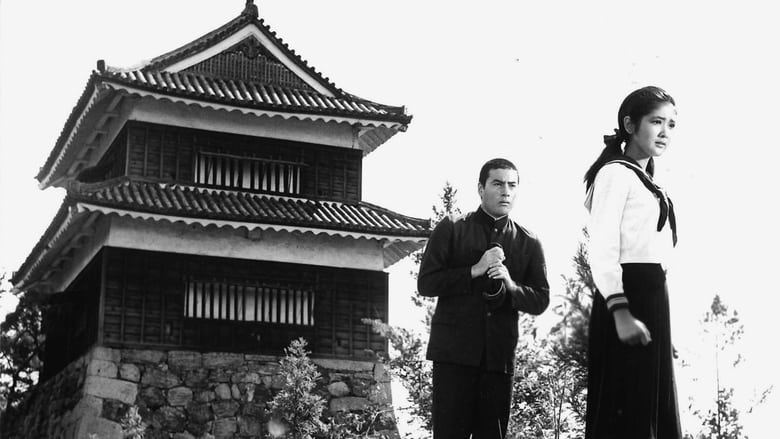

刺青一代 Tattooed Life (1965)

Worth it if only for the genre/style shift in the finale.

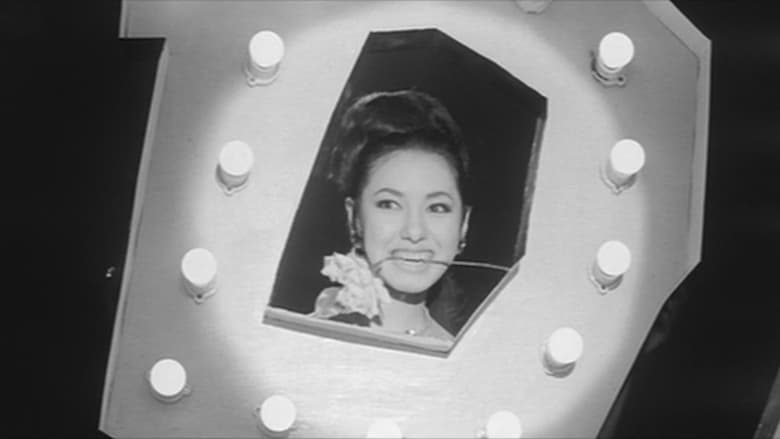

殺しの烙印 Branded to Kill (1967)

I first watched this in 2008. It was the first Suzuki film I’d seen, and was the seed for this year’s Artist of the Year selection. It’s hard for me to neutrally assess this, since it clearly left an impact on me then. It was nice seeing so many motifs from earlier films reappear here, even if I’m more impressed with their utilization in the earlier films. It’s remarkable how otherwise stylistically distinct it is from his other Nikkatsu work.

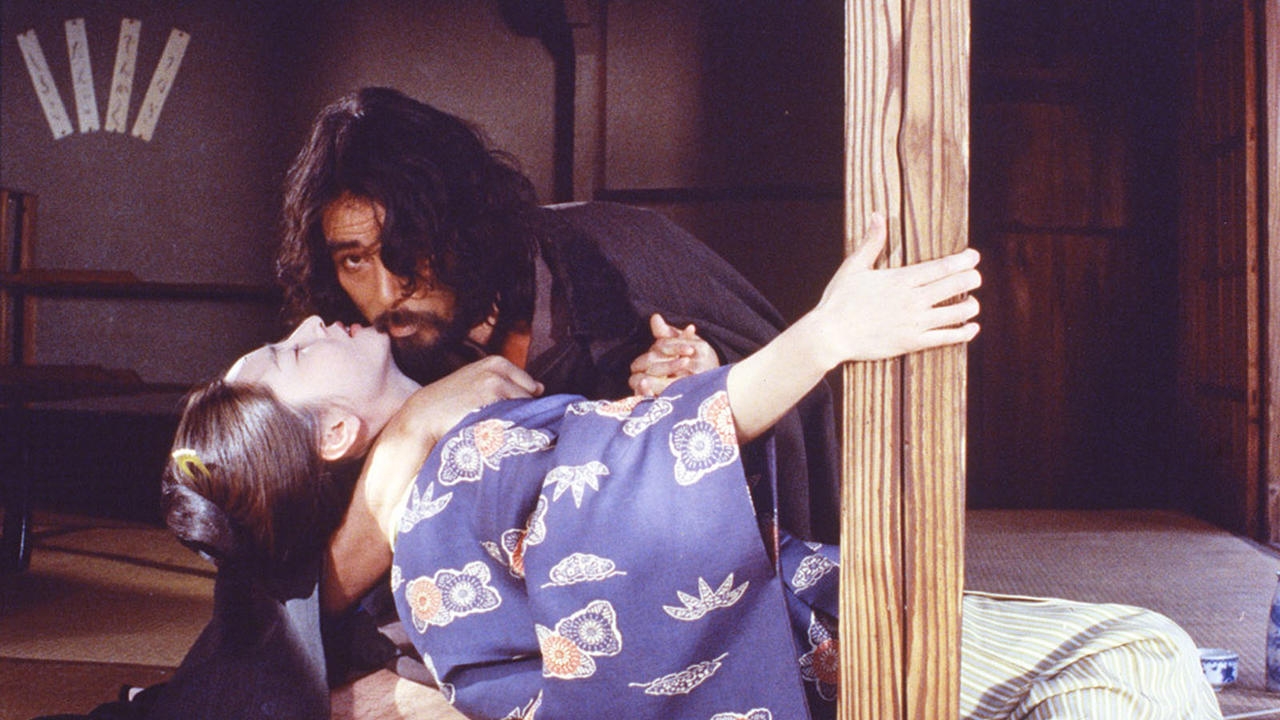

ツィゴイネルワイゼン Zigeunerweisen (1980)

Additionally read the source short story, The Sarasate Disk

I keep returning to this one. While it didn’t grab me in the moment, it’s certainly the Suzuki film I’ve spent the most time thinking about.

ピストルオペラ Pistol Opera (2001)

It’s so good seeing Suzuki work in the blown out early 2000s digital video aesthetic. I might like this even more than the coloring of Tokyo Drifter.