Artist of the Year 2023: Spike Lee

When I embark on a new year’s Artist of the Year project, I’m searching for an angle of approach to the material. What are the set of questions I want to be asking myself after each of Spike Lee’s films? And with a figure like Lee, someone who has been examined and scrutinized extensively for decades, asking if that territory’s already been thoroughly charted.

This isn’t to claim that I’m trying to contribute novel scholarship to the field. Rather, I want to grab a question that doesn’t already have easy-to-find answers and wrestle with it for several months. If writing is a tool for thinking, then this project is a challenge of sustained attention and examination. And the only way to maintain momentum in that pursuit is to keep my mind stimulated, and “something kind of novel” satisfies that.

One piece of writing that loomed large during my time with Spike was Wahneema Lubiano’s fantastic But Compared To What. It was important for me, as someone who already had a retrospective familiarity with Spike’s work, to witness contemporary critiques of his early work from Black writers. There’s a fogginess that surrounds Spike: a combination of self-perpetuated myth, racist dismissal, cynical PR, and contemporary reevaluation that can mislead us into a false understanding of history. The real responses were both shittier and far more thoughtful (distinctly, of course) than I might have expected sitting in 2023.

The angle I landed on was in considering Spike’s conflictual positions on Black image-making and Black-image making.

School Daze 1988

Just so full of stuff, so much so that everything gets rather thin. In doing so, becomes a document of all the forms of Blackness Spike can make fit in two hours. Which then makes the absences (e.g. homosexuality) particularly interesting.

School Daze is an interesting case study of Lee’s consistent insistence on having substantial Black representation in his crews. Lee has published production diaries/behind-the-scenes books for a number of his films, generally containing the screenplay, some interviews, and a lot of dubious claims made by the man himself. Even if manipulative, their contents are still revealing, and Uplift The Race, the one published for School Daze, even more so.

In it, production manager Matia Karrell wrote about the challenge of Spike’s hiring people without experience, sometimes having people without experience lead those with far more. Throughout Karrell’s segment, there isn’t any mention of race, but it’s not a stretch to understand that that was a key contributing factor to the inexperience. The one department that Karrell names is costuming. With the privilege of hindsight, we now know that that inexperienced costume designer was the 4x Oscar nominated (2 wins) designer Ruth E. Carter working on her first feature film.

It’d be tempting to read this anecdote as vindication for Spike. But I think that’s too simple of a story. That story is still predicated on Carter being “one of the good ones”. More damning is that, if someone of Carter’s ability or potential required such disruptive maneuvers to build experience and a reputation, how insurmountable must the walls have been (still be?) for a Black costume designer of median ability?

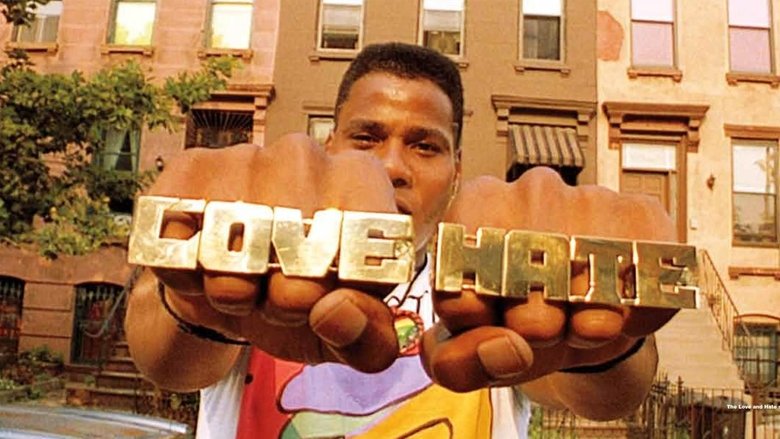

Do the Right Thing 1989

Struck by the opening. Visually exuberant. Also gratuitous in length and objectifying of Rosie Perez. Spike is a phenomenal visual artist with some obvious bad tendencies.

On rewatch, so much easier to pay attention to and appreciate the density of named characters in the background of scenes where they’re not the focus. Really sells the one-block, one-day setting.

Much warmer colors than I remember than the 35mm print I saw.

Do the Right Thing 1989

Rewatched with the 1995 commentary from by Spike & Joie Lee, Ernest Dickerson, and Wynn Thomas.

Two surprises: Smiley wasn’t included until late drafts, despite being a really crucial character, in my view. The best scene (Sal & Pino chatting) was largely improvised once Smiley appears.

Both more fuel for my cinema as art of contingency and coincidence platform.

Mo' Better Blues 1990

I didn’t enjoy it, but setting that aside, it’s still a delightfully rich text.

Particularly, I read this through the lens of Spike Lee’s relationship to Black Capitalism. There’s been plenty written that Lee is a shitty boss like other studio bosses, but Black. Bleek embodies a lot of that, stifling the careers of his employees, being capricious.

But Bleek is also framed as a put-upon worker, not getting his due from the club owners. Lee’s always remarkably even-handed in the treatment of his characters, so it can be hard to glean personal positions.

Mo' Better Blues 1990

Rewatched with commentary by K. Austin Collins

Something interesting in here about the way black middle-class professionals remain tethered to not-so-professional past or family that produces vulnerability. In Jungle Fever, too.

Also, just some gorgeous shots. The rotating dolly is inspired, but the double dolly shots are wack.

Despite not enjoying it in the moment (just see my annotation above), Mo’ Better Blues has stuck with me more than most of Lee’s. The weaker plotting of the romances fades, leaving only the mesmerizing visuals of those same romances. There’s a tempting semi-autobiographical reading, but more than anything, it’s the story of an artist contending with the complexities of making art. And due to that, it’s the film I’ve referenced most in conversation with friends navigating similar waters.

To a certain extent, this can be seen as a precursor to my beloved Bamboozled. Lee’s reverence for his father’s art is on full display here, but Lee has more specific things to say when the arena shifts to his home turf of the moving image.

Jungle Fever 1991

The movie ultimately doesn’t care about interracial relationships. This shouldn’t surprise, given Lee’s lack of experience, and noted opposition at the time (and maybe still?). Instead, the film cares far more about how the existence of these relationships provokes anxieties and insecurities in others.

Flipper and, especially, Angie don’t share what they really think about their relationship. Flipper says things (Angie isn’t afforded even that), but those statements aren’t really backed up or reinforced in any other way. Because Lee has nothing to say here.

Malcolm X 1992

I’m not fond of biopics. So this was already at a disadvantage.

Lee’s characters often operate primarily on a symbolic level, so seeing Malcolm so developed, constantly evolving, is a nice change. It helps, of course, that he was a real man. But no man’s life can be compressed into the length of a feature film without omission, abbreviation, and untruth.

The most powerful image comes at the end, the glimpse of Malcolm, in color, behind a video camera, smiling, filming himself. In that moment, it becomes easy to forgive the previous myth-making, and recognize that he was just (in all the complexity that entails) a man.

Our first interesting case study for Black image-making not necessarily aligning with Black-image making. Spike Lee was very public in his opposition to the original plans to have this film directed by Norman Jewison, and that only a Black director could do it right. Later, there was vocal concern about Lee being that director. Was Lee both capable and likely to bring something novel to the film? In the end, as noted by bell hooks, Lee’s version wasn’t meaningfully different from the portrayal that any white director would have done, by lfattening and deradicalizing the man, except it centered Lee (both in front of and behind the camera).

This is maybe one of our first examples of campaigning around Black image-making really being more about Lee’s personal opportunities and enrichment than anything else.

Crooklyn 1994

A rewatch. I just loved spending time with this family. As one of four children, with one sister among us, there’s so much in the kids’ dynamic that stirs up memories of summer of the four of us at home.

Clockers 1995

Challenging to watch this after Strapped. While Clockers has almost all the artistry, the story itself, of a man caught between the hood and the cops, I find far superior in Strapped.

It’s also interesting that both films began as works (Clockers the book, Strapped’s original screenplay) that centered the cop, and the director actively re-centered the narrative. Strike just has a lot less stuff going on than Diquan. He’s an object in the actions of other subjects, rarely a subject himself.

Lee had spoken negatively about the hood film genre for years, particularly in the image of the Black man that such films put out into the world, arguably for the consumption of white audiences. His turnaround is an concise example of the interplay of his ideals and the market realities of being a working director.

Get on the Bus 1996

I was excited for this, because of the way it embodied a “black polyvocality” I’ve been thinking about lately. And on a surface level it does, but unfortunately so many of the worldviews expressed by these characters remain surface level.

As an example: a passenger, raised by his white mother in a white milieu, has his blackness questioned; a cousin of a question I’ve grappled with my whole life. Rather than engaging with it, the question is posed by a fool who gets details of slavery wrong, and so his provocation is dismissed. There is a stronger version of this debate that’s hidden, like so many of the other conflicts on the bus.

Girl 6 1996

Wild that Tarantino is in this in this way. Especially knowing Rapaport’s character in Bamboozled.

Along with Crooklyn, a strong contrast of Lee’s handling of female characters when he’s not the writer.

Seems at its most alive when transplanting the protagonist into historical roles/films, which permits a formal playfulness. There’s also some nice use of digital video when we see the callers, a nice prelude to Bamboozled.

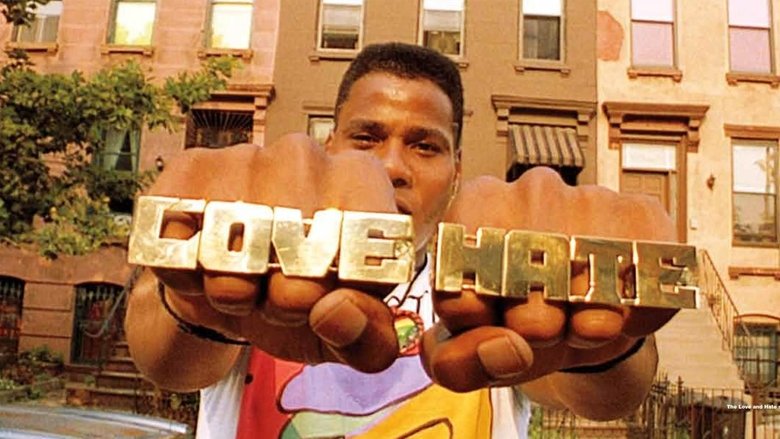

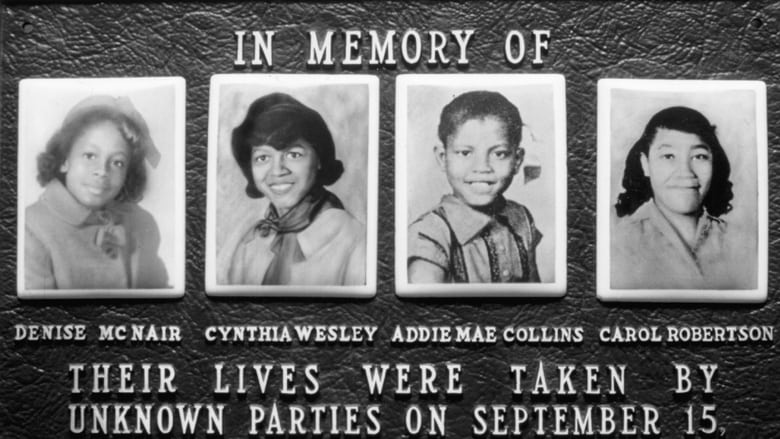

4 Little Girls 1997

I was shocked at the actual usage/depiction of the girls’ bodies. It’s handled respectfully, and very briefly, but still.

Continues some of the effectiveness with the archive that I mentioned in Malcolm X, and given the different crews, I have to imagine that that’s Spike.

He Got Game 1998

Uncharacteristically high concept for Spike Lee films I’ve seen. And I have to admit, the concept is quite compelling.

There’s a bunch of stuff that doesn’t work: Ray Allen can’t act, Mila Jovovich’s character doesn’t really go anywhere. But then, there’s the absolutely riveting climactic 1 on 1, and I forgive almost everything else.

Summer of Sam 1999

Perhaps would have been stronger with all of the actual Son of Sam parts removed. What’s interesting here is the portrait of this time, place, and the people living through it. Everything about the Son of Sam himself feels out of place, and detrimental, to that feeling.

This has grown on me in the weeks since watching, particularly the depiction of Ritchie and Ruby attempting to escape the (reductive and almost offensive) pathologies of their Italian-American enclave. There was a sensitivity in the portrayal of the sex work and general outsiderness that felt new within Lee’s work.

The Original Kings of Comedy 2000

Interesting seeing one of Spike Lee’s editing tics (the double cut) show up in a non-narrative setting. Using it here gives us the privilege of a joke both in close-up, along with the crowd reaction.

Outside of that, there’s an interesting pairing with Bamboozled here, in the presentation of an act on stage, in Bernie Mac’s reflections on white people in the audience signalling having made it, and in expanding on Paul Mooney’s arc in that movie. There’s a big world of black entertainment for black audiences in the modern Chitlin Circuit, as proven by this movie’s box office receipts.

Bamboozled 2000

Third watch, thinking about the unfair treatment of the Mau Mau. While Big Blak Africa gets to feature in possibly my favorite (non-montage) scene with Sloane in her home, the Mau Mau are largely treated like a joke, which is strange.

Spike Lee has talked at length about his being raised in a culture of jazz, not hip hop, but still sought Public Enemy for Do The Right Thing, featuring Fight The Power in a number of sequences. And Public Enemy released Burn Hollywood Burn a decade before Bamboozled, covering some similar territory. But in isolation, Bamboozled is merciless towards their ilk.

A Huey P. Newton Story 2001

I’ve read a lot by, and about, Newton this year, so having this come up during my Spike Lee watch was serendipitous.

There’s something offputting about embodying a recent historical figure, a still contested figure, and editorializing while cloaked in their persona. At moments, the comedic characters that Smith has played break the surface of an otherwise great performance, and you realize you’re looking at a puddle, not the sky. Newton could be goofy! But the character that I saw on stage in those moments seemed more out of Deep Cover than West Oakland.

25th Hour 2002

There wasn’t enough here for me. The post-9/11 aspect is easily the strongest element, contributing several powerful scenes, top among them being the conversation in front of the view from Frank’s condo. And there’s almost some connection that coalesces between pre-9/11 New York and choosing to remember someone a particular way. Or the life that almost didn’t happen. But I don’t think it manages it.

Instead, it feels like reheated Spike Lee. The double (triple! quadruple!) cuts at the start. The obligatory double dollies. Even the fuck monologue feels like a bad sequel to a similar scene in Do The Right Thing.

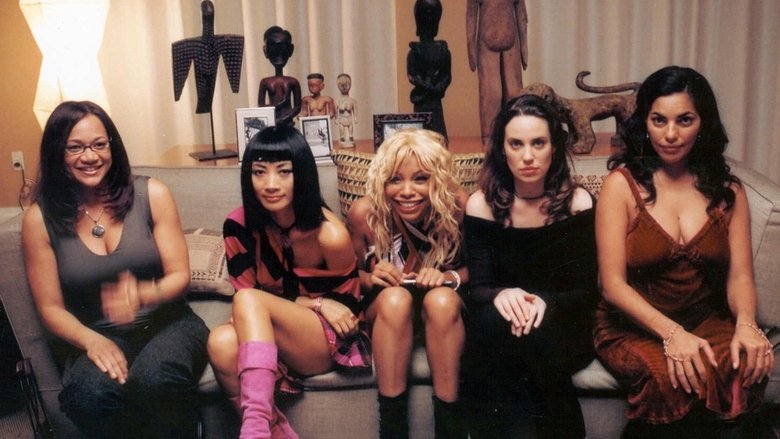

She Hate Me 2004

Tonally erratic, but never not a good time. It actually reminded me of Jungle Fever in its smashing together of two plots that have no business being together, but the lack of self-seriousness here means it works. The stakes for Jack never seem that high after the first 10 minutes, and that makes it easier to just ride along with Spike.

There’s one unfortunate kiss that didn’t need to exist. Setting it aside, I’m always excited to see unconventional families succeed on-screen.

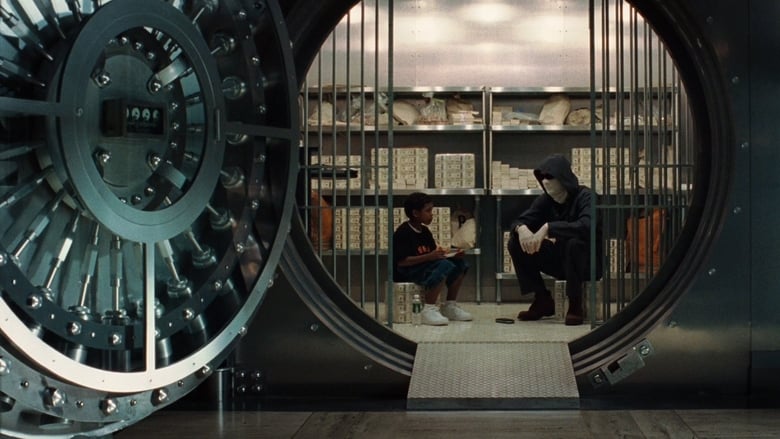

Inside Man 2006

In the large, feels even less like a Spike Lee film than I remembered. One detail that stood out as noticeably “Spike” was the videogame the kid plays, echoing the embarrassing game (and politics around games) featured in Clockers.

This movie is still a lot of fun, even (especially?) on a rewatch.

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts 2006

Earns its 4 hour runtime by doing something perhaps unintentional with its two halves. The first half covers the story I already knew: the story as covered by the media for those of us far from it. By the end of Act 2, I asked myself “what is there left to tell?”.

Acts 3 and 4 were the story perhaps less known about what came, or didn’t come, next. There’s a shock when watching something on streaming, and thinking you’ve come to the conclusion of the story, only to discover upon pausing that you’re only about halfway through. This accomplishes something similar via two parts (though the runtime isn’t a surprise).

If God Is Willing and da Creek Don't Rise 2010

Unlike the first entry, this doesn’t earn its runtime. Where the first was focused, this has a few too many things to focus on. BP, FEMA trailer formaldeyde, the Super Bowl, hospitals. I appreciate returning to the scene, and continually following up on a story. But there are just too many stories to cover. A city is a complex beast, and attempting to capture its essence is perhaps folly.

Miracle at St. Anna 2008

Has a fantastic opening that’s ultimately let down by everything that followed. The payoffs for the mysteries established early on (and one late one) just don’t carry the weight that one could imagine. And the ending sequence is rather embarrassing.

Red Hook Summer 2012

Calling this a reverse Crooklyn invites a harsh comparison for these nonprofessional child actors. And they waste the stellar adult performances, namely Peters and Domingo (the best double dolly!).

Too much cranky-old-man Spike in the writing, particularly around the iPad and technology broadly, that’s unmotivated and irrelevant. This culminates in the final sequence, where Flik’s memories are shown with the language of nostalgia of Lee’s generation, not Flik’s. Would have been far better to show a sequence of Instagram-filtered photos, as if Chazz were looking at them herself.

Passing Strange 2009

I’d been skeptical of filmed stage productions, as they’re designed around a distant audience, capable of directing attention anywhere on stage. And that calls for very different techniques that something shot with a camera.

Lee solves that by crafting filmic scenes with the stage production as raw material. Lens choices, color grading, and framing with impossible (audience) angles means we see something better than we might have on Broadway, by virtue of using cinematic language on top of stage language.

Oldboy 2013

Pointedly not a “Spike Lee Joint”, as indicated by the credits, and that probably tells us all we need to know. An uninspired remake of a movie I’ve already soured on.

Da Sweet Blood of Jesus 2014

Ganja & Hess bled of its visual poetry and eroticism. On that second point, it was actually sexually regressive.

Where this does add of deviate from the original, it’s almost uniformly worse for the change.

Chi-Raq 2015

I admire its audacity. And the first ten to fifteen minutes were promising.

But then it degrades into moments of stilted didacticism. They’re politically obvious and patronizing, and lack any of the even-handedness that characterizes much of Spike’s earlier writing, and earlier adaptations like Clockers.

Throw Like A Girl 2014

A delightful detail in this, that shows up in Lee’s other documentaries, too, is his casual shouting of questions. There’s this sense of an easy interaction between interviewer and subject that’s touching. Like when he ribs Mo’ne’s step-dad for not encouraging sports sooner.

Rodney King 2017

A powerful performance in service of modest material. There’s a strange meanspiritedness toward King, particularly around his lack of formal education. There’s a story to be told about King, those two days of his life, and his death. But this can’t focus on that. The Latasha Harlins digression, for example, isn’t really part of King’s story. It’s context for the uprising, sure, but it doesn’t contribute to the story here.

Finally, closing with “I can’t breathe” connects King to Eric Garner, who was killed earlier that year (the show is from 2014, but the filmed version is 2017). That connection, apt, becomes concerning with the “he was no angel” framing of the earlier 50 minutes.

BlacKkKlansman 2018

Jarring to hear Blanchard’s score from When The Levees Broke in the final narrative sequence.

Flirts with some interesting/provocative juxtapositions (klan and cop, black power and white power) but the genre material, undercover police thriller, doesn’t engage those themes the way e.g. Deep Cover manages the same.

As a political object of its moment, it’s admirable. The closing non-fiction footage does make the subtext text in a way that perhaps wasn’t essential, but adds to its urgency.

What an opening!

Pass Over 2018

Feels almost like an apology for Chi-Raq, given its location, and Kitch’s Chance hat (Chance was a vocal critic of the film).

There’s a vagueness to the events that primes you for an allegorical reading, but the cop is pure literalness. There’s a risk with this material that it lacks enough specifics to convey anything effectively, or that that vagueness is the sign of an unsure author. The fact that there’ve been at least two script revisions since draws more attention to that last possibility.

Regardless, it affected me in the moment.

Da 5 Bloods 2020

There are moments where Delroy Lindo’s performance triggers bad memories of folks in my life dealing with some shit, and I’m wowed (e.g. the fruit boats). But then there are moments where I have no comprehension of who this character is, changing with the narrative needs of the moment. And maybe that has some purpose, but it’s frustrating.

Similar confusion appears in other places, over whether or not there’s any solidarity between the Vietnamese and Black soldiers, or if service is honorable or not. This doesn’t so much pose questions to debate, so much as point and shrug

So who is Spike Lee?

There are excellent critics out there who, even today, speak of Spike Lee as someone with radical politics. It’s always surprising when I hear that, as it’s never been clear to me that that was true at any point in his career. Throughout his career he’s consistently been the target of critics who took issue with his alliance with white capital, his behavior as a boss himself, his undeft handling of genuinely radical figures, his treatment of women generally, and his monopolization of attention and appetite for Black stories. Spike Lee doesn’t have radical politics, and there isn’t an indication that he necessarily has a coherent politics at all. And that’s fine. I think turning to any artist for ideological direction is fraught. Rather, Lee is actually rather good at revealing to audiences things even he doesn’t seem to know1.

No, the Spike Lee I’ve seen in watching the above movies is one who has wrestled with two impulses, that of promoting Black image-making, and the responsibility of Black-image making. These twin motives help explain the (shouldn’t have been) startling conservatism of Chi-Raq and to a lesser extent BlacKkKlansman, Lee’s harshness to other filmmakers or performers when he believes they’re doing a disservice to Black America through their art, and also why I think Bamboozled is Spike’s most effective film.

Spike Lee’s feuding with other film figures derives from this dilemma. For white artists, the offense is telling stories that Black filmmakers should instead. A cynical reader could infer that means Spike himself (and sometimes that is the case). When calling out other Black artists, the offense is almost always the harm done to the image of Black Americans, whether that be co-starring in Soul Man or creating Madea. This gesture towards respectability surfaces in Chi-Raq where Spike perhaps inadvertently echoes right-wing talking points about Black-on-Black violence, and gives comparatively little time to the systemic causes of that violence. Similarly, BlacKkKlansman idealizes police work, where addressing anti-black speech (not even violence) is a matter of rooting out bad apples. Within two years, the George Floyd uprisings would reframe the simplistic understanding of police as agents of positive change.

I don’t care to expand any further on the things I dislike about Lee’s work, since it’s far less interesting than the things I love. Beyond his visual abilities, I particularly appreciate how these two forms of image creation manifest in Bamboozled and Girl 6. Both are expressly interested in image making (TV and film respectively), and specifically the challenge of existing as a Black individual, telling Black stories, in such institutions. Lee didn’t write Girl 6, but its themes speak to preoccupations of his that would crystallize in the incredible and messy Bamboozled.

Despite the fury that clearly lies underneath that film, there’s also a certain kind of ambivalence and grace that permeates it. Yes, the material can be degrading. But underneath that burnt cork are world-class performers doing incredible work, deserving of their accolades as well as askance looks for reinforcing harmful stereotypes for white pleasure. Better than any other of Lee’s films, Bamboozled is able to articulate a kind of system, even if it isn’t able to name it, that reproduces these dynamics across 100 years of film history, and more even before the advent of film.

1 This concept was introduced to me in Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler by an author character who aspires to that sort of impact.

While used to quite different effect, the still photography (by Spike’s brother David) has echoes of the still sequences in Gordon Parks Jr.’s work.

Exciting in its visual confidence, via conspicous lighting, framing, and lens selection. Structurally too, with the faux-documentary confessionals. Politically there is something weird about Spike Lee’s stated interest in the defense of black men with this film simultaneous with the flattened portrayal of black women.