Artist of the Year 2024: Peter Weir

Incredible Floridas 1972

When at the symphony, I sometimes struggle to calm my mind, or give myself something to visually focus on. Here, Weir decorates the music with images, distracting me just enough to counter-intuitively highlight Meale’s composition.

Whatever Happened To Green Valley? 1974

I’m reminded of the expression of “affectionate proximity” in an essay within Capitalism and the Camera. While the home movies aren’t necessarily any more truthful than those made by outsiders, they grant subjecthood to the former objects of discussion. They’re valuable, if only for that.

The Cars That Ate Paris 1974

There’s a “leopards eating people’s faces” angle to this that I like. A village that survives on the vehicular murder and pillage of strangers empowers an especially violent subset that ultimately destroys that same society and their veneer of alleged civility.

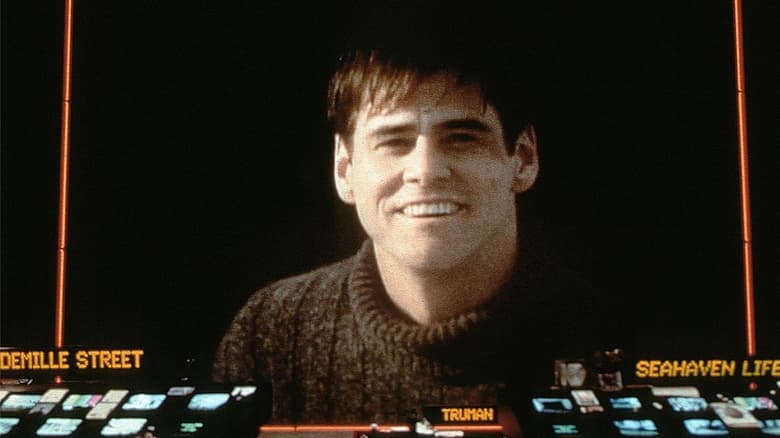

The Truman Show 1998

My first Artist of the Year viewing to occur in a theater!

A rewatch so temporally removed from my first viewing that it’s effectively brand new. I don’t know what child me got out of see this, but now, as an adult, the unsettling layering of performance(s), and the image of a turned-away Carrey muttering “you didn’t have a camera in my head” are unshakeable.

The Last Wave 1977

Despite the good intentions indicated in the commentary, and the implicit sign-off of the aboriginal actors, I’m still somewhat uncomfortable about the focal whiteness of this. There’s a particular kind of white fantasy of being a member of the other, despite appearances (in this case, being a spiritual being). This is further amplified by the lead actor’s purported Native American heritage.

The Plumber 1979

Ultimately, I didn’t get a lot out of this. But the film seems to be a good example of the fraught nature of message delivery by film. There are a not insignificant number of reviews that, rather than reading the film as being critical of Jill’s behavior, instead endorse it. That all of the other characters are “gaslighting” her when they claim that the plumber is actually a nice guy. That Jill’s framing him is righteous.

The movie isn’t terribly subtle about Jill’s disconnection from both the poor and non-white people, and it doesn’t take much to connect the dots between that and her paranoia. Identification is strong.

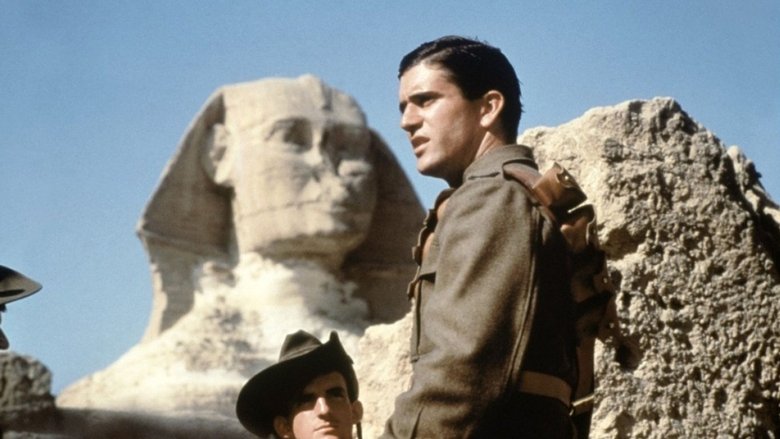

The Year of Living Dangerously 1982

When it’s at its best, it’s exploring the virtuous and wicked ways to bear witness to the world beyond our own borders. When at its worst, it’s depicting an unconvincing and uninteresting romance (which admittedly produces interesting tensions within the film’s stronger side).

The specific proportions of good and bad at play here end up distilling a people, and a nation, down to an accessory for an Australian man’s self-actualization. Reading the synopsis of the source book, it seems this balance is particular to the film adaptation.

Witness 1985

Another wonderful culture-clash film by Weir.

Glad the police procedural serves as mere scaffolding for the romance, planted in mutual care, and doomed by its likely mutual exotification. I didn’t understand Ford as sexy until here. Every look of McGillis’s and Ford’s is an enchanting invitation for transgression.

Love also the many moments of explicit non-dialogue. Samuel’s eyelines and pointing. The erecting of the barn. Also has my new favorite cinema laugh: Eli’s laugh at Book’s comment about never holding a teet this big.

The Mosquito Coast 1986

Perhaps in 1986 Allie would be recognizable as a human, but in 2024 this guy is wholly alien. A grab bag of grandiosities that don’t all make sense in one person simultaneously, it mostly makes this about one guy who sucks.

And not even a guy who’s wrong! Some of those grandiosities are indulged in a way that undercuts the characterization. As if Allie is largely correct that he’s in the right and it’s the world dragging him down.

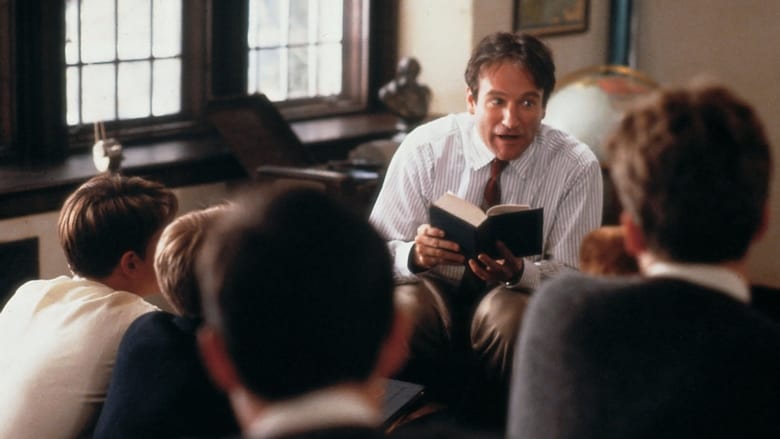

Dead Poets Society 1989

Better in concept than execution. Nothing that Keating does in the class room, beyond the page tearing, really conveys a sense of transgression and revelation for the students. We’re just asked to accept that poetry in silly voices stirs the spirit.

Green Card 1990

MacDowell’s reign of terror continues. I swear there was an instance where she smashed two lines together as if she missed the period, and they kept that take amongst all of the other options.

Fearless 1993

Sad that I missed this much earlier when Joe Talbot was screening it at the Roxie.

Compelling portrait of two approaches to trauma, one of which is coated in an unstable magic. We’re induced to believe, against all rationality, often embodied by the airline-issued psychiatrist. Ends a bit too pat for my tastes.